Controlled airspace infringements caused by general aviation (GA) pilots is a fascinating topic, as it is a consistent problem in the UK’s airspace, evident as one of the most common occurring incident types. Within this blog I will take you through the background of airspace infringements in the UK, my key findings and analysis of what causal factors are involved, and what are my proposed recommendations to further mitigate this problem.

I have a personal interest in this topic as I conducted pieces of work on my placement year around the topic of infringement events. It became evident to me that this was a real issue, and with each event being different (in relation to location, severity, and consequences), this was a topic I wanted to investigate further. During my final year at university, my dissertation was titled General Aviation Airspace Infringements – Identifying Causal Factors and Mitigations. I utilised the SHELL model to highlight these factors, which were identified through a mixture of primary and secondary data.

What are Airspace Infringements?

An airspace infringement is defined as “the unauthorised entry of an aircraft into notified airspace… including controlled airspace, prohibited or restricted airspace, active danger areas, aerodrome traffic zones (ATZ), radio mandatory zones (RMZ) or transponder mandatory zones (TMZ)”[1].

The table below shows that between 2017 and 2018 there was an increase in infringement events by 17%. In 2019 there was a decrease in events compared to 2018 by 6%. The current data available for 2022 is that the total number of infringements between January and May is 520 incidents, which is greater than the number of incidents that occurred in 2019 for the same time period. As it is comparable and is likely to fall within the range seen in the table below, it is suggesting that even if minor increases or decreases occur year on year, the problem is not being mitigated at a significant rate.

| Year | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| Total reported infringements | 1162 | 1358 | 1271 | 753 | 1057 |

| Control Areas (CTA) (includes Airways) | 812* | 706** | 411 | 294 | 350 |

| Terminal Manoeuvring Area (TMA) | *included in 2017 CTA figure | **included in 2018 CTA figure | 294 | 130 | 176 |

| Control Zone (CTR) | *included in 2017 CTA figure | 285 | 289 | 194 | 291 |

| Aerodrome Traffic Zone (ATZ) | 97 | 130 | 100 | 63 | 93 |

| Restricted / Prohibited / Danger Areas | 81 *** | 87 *** | 54 | 39 | 79 |

| Temporary Restricted / Prohibited / Danger Areas | *** included in 2017 Restricted / Prohibited / Danger Areas | *** included in 2018 Restricted / Prohibited / Danger Areas | 13 | 3 | 16 |

| Transponder Mandatory Zone (TMZ) | 57 | 76 | 46 | 15 | 35 |

| Radio Mandatory Zone (RMZ) | 115 | 74 | 48 | 14 | 11 |

| Controlled Airspace – Temporary (CAS-T) | 3 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Upper Information Region (UIR) | 4 |

[2] https://airspacesafety.com/statistics/

Airspace infringements are a safety issue because the worst-case scenario of an infringement into controlled airspace is a mid-air collision. Even though it is unlikely for a collision to occur from an airspace infringement, there is still the possibility, as well as Loss of Separation and Airprox incidents. A separation minimum is in place to keep aircraft separated within controlled airspace, and if this separation minimum is not met, this is called a Loss of Separation (LOS)[3]. An Airprox can be described as “a situation in which, in the opinion of a pilot or air traffic services personnel, the distance between aircraft, as well as their relative positions and speed, have been such that the safety of the aircraft involved may have been compromised”[4].

The difference between a LOS and an Airprox incident is that during a LOS event, the controller is usually in contact with the aircraft involved. During an Airprox incident, there are one or more unknown entities causing or involved in a safety incident. An airprox incident can lead to a LOS incident and would generally be considered worse than a LOS between known aircraft, as with Airprox there is a greater degree of uncertainty due to the controller not being able to contact or identify the entity fully. An Airprox can be caused by anything unidentifiable to a pilot in the sky, or on radar for the air traffic controller. Examples of such unidentifiable objects include drones, balloons, carrier bags and more.

The SHELL Model and Causal Factors

A causal factor can be defined as an unplanned, unintended contributor to an incident, where if not evident, the event could have been prevented or at a minimum reduced its severity or frequency.

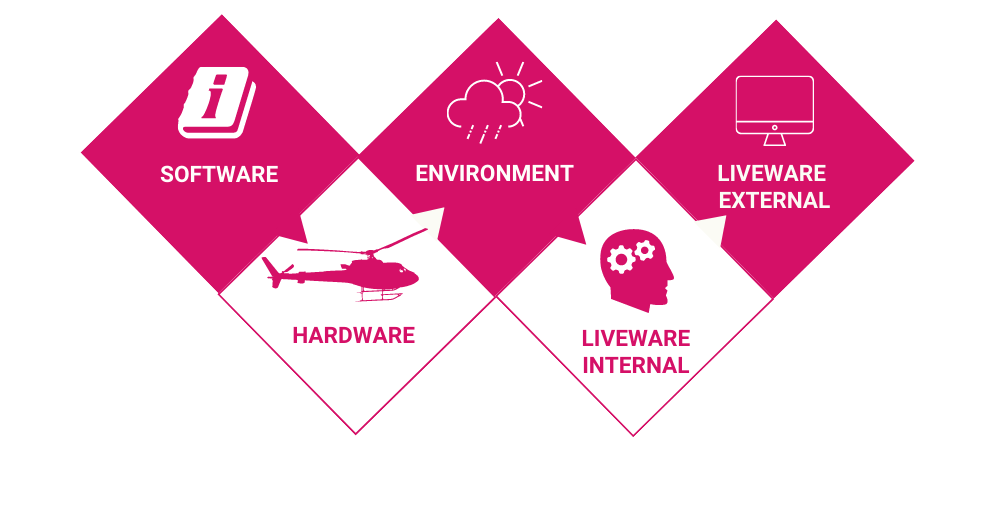

The SHELL model, illustrated in the figure below, is used to clarify the scope of aviation human factors and assist in understanding and evaluating the human factor relationship between the human components in the system and the other human and automated components. The model consists of five different interactive, overarching elements: Software, Hardware, Environment, Liveware – Internal and Liveware – External[5]. The SHELL model addresses the interactive nature of human relationships with other components of the system but does not include any aspects outside of human factors. Thus, no factors relating to hardware affecting hardware, or software affecting software, etc are included.

The Shell Model

The advantage of this model is that it provides an insight into the interaction of the human elements with other components of the system, including other humans. This creates an awareness of the influences on the human components of the system. The SHELL model enables future prevention of accidents and incidents, as well as being useful in reducing errors.

The disadvantage of this model is that it only relates to human factors and does not consider factors outside of that and is only intended to be used as a basic aid to understand human factors.

SHELL Model Results

As stated earlier, within my dissertation causal factors were identified via journal articles, statistical reports, and interviews. Interviews were conducted with pilots, air traffic controllers and safety investigators. I created an initial SHELL model from the literature I had reviewed and asked the interview participants to highlight which factors they felt were most prevalent within each component of the model. Furthermore, I asked the participants to state any other factors that they may feel are relevant to airspace infringements. The final results are summarised in the table below. 33 factors were identified as causes for airspace infringements within UK airspace. The factors in bold were new factors identified by the interview participants.

Software |

|

Hardware |

|

Environment |

|

Liveware – Internal |

|

Liveware – External |

For Software, the two main factors highlighted by participants were pre-planning and lack of reading NOTAMs. Pre-planning was highlighted by all five participants, suggesting this a factor that should be examined by the GA community, as before each flight, pre-planning should occur, and should be in-depth to reduce the risk of an infringement occurring. The lack of reading NOTAMs as a factor indicates that GA pilots may miss vital information in relation to airspace changes or restrictions. This could gravely increase the chances of an infringement, thus suggesting that the reading of NOTAMs should always be conducted, and possibly incorporated within the pre-planning aspect before a flight.

For Hardware, the main factor identified by all five participants was failure to use moving maps correctly. This is a key factor because like any piece of equipment or tool on an aircraft, if the pilot does not know how to use it correctly or effectively, it could lead to a possible controlled airspace infringement.

The Environmental factor that was highlighted by all participants was meteorological conditions. This suggests that depending on the pilot’s qualifications and aircraft capabilities, the meteorological conditions could lead to an infringement. This can be due to diverting to avoid bad weather, or being caught by wind, causing a controlled airspace infringement.

Liveware Internal consisted of many factors, with lack of use of a Frequency Monitoring Code being identified as the most significant contributing factor to an infringement by four out of five participants. This factor suggests that if the use of these codes were used by pilots more regularly, there may be a reduction in infringements, as pilots will be hearing air traffic control instructions, as well as being able to ask questions. This may decrease the likelihood of that individual pilot infringing.

For Liveware External, the main factor identified by four out of five participants was distraction. This is in relation to single pilot operations, operations with passengers and during student training. This is a key factor as distraction could lead to a lapse in concentration, leading to airspace infringements occurring. Furthermore, distraction could allow for information and possible actions within the cockpit to missed or forgotten, increasing the chance of a safety incident occurring.

What is the Future of Airspace Infringements in the UK?

Airspace Infringements are always going to occur, as it is an error that is bound to happen. With all the factors identified, it will be near impossible to eradicate all of them in a financially and just way. Below are recommendations for how infringements could be mitigated in the future:

-

-

- Infringement events can be reduced by mandating that all new pilots learn how to use moving maps, even though not every pilot or aircraft will utilise a moving map. Statistics show that their incorrect has led to a considerable number of infringements. Furthermore, moving map training courses could be made available at flight clubs, possibly in conjunction with the moving map creators. This would enable all pilots of varying experience to learn how to use moving maps effectively and correctly.

- If the regulator or flight clubs made it mandatory for pilots to attend numerous safety awareness meetings a year (one every quarter for example), it would enable pilots to stay current with any airspace changes and any possible lesson learning from events that have recently occurred. Making these sessions mandatory will enable knowledge sharing at a greater level within the General Aviation community.

- Regulators and ANSPs should look to work together to provide statistics and data relating to airfields with the most infringing pilots and when the most infringements occur. This information could be vital, as it would highlight the key airfields that need more education around airspace boundaries, as well as effectively producing lesson learning material during months where infringements occur the most. This enables greater education and learning materials to be produced at the key airfields, as well as reducing the possibility of infringements during months that are statistically high for infringement events.

- Finally, there should be research undertaken to identify if there are any other countries or regions that have managed to reduce the frequency of this incident type. This research could identify any possible mitigation actions that the regulator may be able to adopt, therefore helping to combat the high number of infringing aircraft.

-

At Think we are always looking at ways we can help improve the safety standards within the industry. Hopefully this blog has given you an insight into one aspect we can assist with, whether it be identifying human factors, to engaging with issues that are faced with the commercial and general aviation communities. With our ever-growing knowledge pool in Safety and Human Factors, contact us today to find out how we can support you on these types of projects.

Author: Kush Shah, Analyst, Think Research

References

[1] https://airspacesafety.com/infringement/#:~:text=An%20airspace%20infringement%20(AI)%20is,transponder%20mandatory%20zones%20(TMZ)

[2] https://airspacesafety.com/statistics/

[3] https://en.lvnl.nl/safety/categories-of-incidents/loss-of-separation#:~:text=Air%20traffic%20control%20is%20responsible,a%20%E2%80%9Closs%20

[4] https://www.caa.co.uk/safety-initiatives-and-resources/aviation-safety-review/airprox/

[5] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2009.05.004

[6] https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-374518-7.00019-5

[7] https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2019.1564589

[9] https://doi.org/10.1080/24#_ftnref8721840.2019.1596744

[10] https://doi.org/10.7771/2159-6670.1185

[11] https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1541931213601480

[12] https://www.easa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/dfu/Airspace%20infringement%20Flyer.pdf

[13] https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-374518-7.00006-7

[14] https://airspacesafety.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/CausalFactorAnalysisofAirspaceIInfringements.pdf

Recent Comments