Not so long ago drones were everywhere – well, people talked about them everywhere. For an ATM specialist it was hard to go to a meeting without someone saying – “but how are we going to accommodate drones?” But, when drones made it to the press it was normally for the wrong reasons – typically disrupting busy airports. So, how do you accommodate drones without them being a nuisance? To answer this question there are three critical observations that need to be understood.

Firstly, “one size does not fit all” really really applies to drones

Drones can be as small as your fist to the size of an aeroplane; capable of only spending 20 minutes in the air before needing a recharge, to high altitude platforms that can be on station for days, weeks or months. So, let’s not pretend that it is a homogenous problem or that the same rules can apply to all drones. When we talk about drones we need to be clear about which market segment we are discussing.

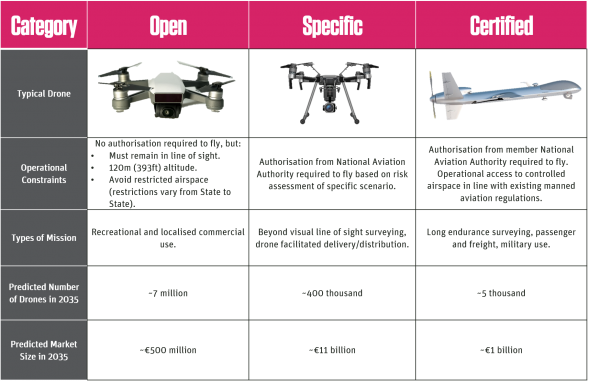

Regulators across the globe are already subdividing by weight or usage. From July 2020, EASA is adopting an operations-based approach to UAS regulation. Operations will be split into “open”, “specific” and “certified” categories as further explored in the table below. This classification already starts to help us understand how different market segments pose different issues for airport operators.

Secondly, the vast majority of drone operations will not be in controlled airspace

Only the certified category are going to be allowed to use controlled airspace. They will follow Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) and be suitably equipped to be “seamless” to Air Traffic Control. Although there are difficulties caused by drones having different flight characteristics to conventional aircraft and the need for different contingency procedures for loss of communications, the accommodation of large certified drones in controlled airspace is not that difficult. The SESAR Programme has already conducted several successful demonstrations.

It becomes more tricky when we start to talk about drones operating in non-segregated airspace and in particular in uncontrolled airspace shared with manned traffic operating under Visual Flight Rules (VFR). Here, the drones will need to electronically replicate the same rules as the pilots apply – this is where Detect and Avoid systems have to come into their own. Drone operations in a mixed manned/unmanned environment is the most difficult to achieve – particularly if the drone operator is not in “line of sight” of the drone.

The truth is that for many of the operations in the open and specific categories – we are talking about airspace which can be effectively segregated or reserved for drones – often referred to as Very Low Level (VLL) airspace. This is where UAS Traffic Management (UTM) or “U-space” as we call it in Europe, is required. Rather like ATM, UTM is not a single concept, but a range of services designed for specific operating environments. Using concepts such as the SORA Guidelines being developed by JARUS, the required services will depend on the nature of the operation and the level of risk.

For example:

a) For leisure users, operating away from restricted areas, very little is required. The use of geo-fencing and electronic or remote ID can help ensure these users remain safe.

b) Where an operator in the specific category wants to perform a long range operation, for example a gas pipe inspection, it may be possible to reserve the required airspace and inform other potential users to stay away.

c) Where multiple drones need to operate within a specific area, for example parcel delivery in urban areas, more sophisticated solutions might be required such as self separation using the same principles of swarms of insects.

Whilst, the development of advanced UTM services may well lead to changes in the way we think about conventional ATM; currently UTM developers can still learn from the ANSPs how to use risk assessment to scale services to be safe and cost efficient.

The drones that are most likely to cause a nuisance to airports, are the larger drones in the open category or the smaller more affordable drones in the specific category.

Thirdly, those with criminal intent do not follow the law

As with all public activities – most people obey the law as a natural part of the social contract of being a member of society. The vast majority of drone users will follow the local rules. Some will need educating. Some will need reminding. But the vast majority will follow the law.

There are simple steps that can be taken at State level to reduce the nuisance effects of drones to airports, for example:

1. Make sure that Remote ID and Geo-fencing are available and have the right information.

2. Put up the signs that say if Drones are prohibited

3. Run national education programmes, so that all drone users know and understand the restrictions.

4. Create a national booking system for the specific category operations

5. Ensure airport operators know when an authorised drone is in the area – no need to stop airport operations when a properly trained operator is working nearby.

But the reality is, no matter what regulations, education programmes and systems are in place, those with criminal intent, by definition, do not follow the law. The last line of defence is to track, identify and neutralise rogue drones. Systems and procedures need to be defined at State and airport level to identify who is responsible for each step – how far can the airport operator go before law enforcement needs to be involved? Speed is of the essence – the cost of airport disruptions add up quickly.

There is no shortage of potential systems – the anti-drone market itself is expected to grow by 20% a year and be worth up to £4bn by the middle of the next decade. There are already over 200 systems available from some 150 firms worldwide offering a wide range of capabilities from trained birds of prey to vehicle-borne systems.

Which brings us back to the first point – one size does not fit all. There are a lot of options. Airport operators have to identify local risks and work with national authorities and law enforcement to define the best combination of procedures and systems for their environment.

Author: Phil Morris, ATM Consultant

Recent Comments